Later 2011…

“More like Too Late For 2011.”

Wow, I really do have procrastination down to an art, don’t I?

“You sure have.”

I seriously can’t believe it’s been more than a year since I’ve published my last blog post. Oh well, recapping 2011 it is!

“Recapping 2011? You’ve made one freaking post!”

Quality over quantity!

A few Highs:

- Still not succumbed to using Twitter (although definitely interested).

- Still not succumbed to joining Facebook.

- Still not into alcohol (which I recently reconfirmed the

hardnasty way). - Still very much enjoying my job as a Business Intelligence developer!

- I’m an uncle now! My nephew is the cutest little fella!

“You are still boring. We get it.”

Most of my early work consisted of me building Cognos reports, but now I’m primarily on the ETL side of the BI profession. As fun as building Cognos reports is, I find working with SSIS and DWH/T-SQL to be more my kind of thing.

He’s 7 months old, frowns a lot and is easily bored. Except when it comes to scratching things: he rarely gets bored of that. So apart from letting him scratch us, which we try not to, we’re running out of ways to entertain him! The world has gained yet another troublemaker, I have little doubt about that.

A few Lows:

- Still haven’t finished my Peer Review blog series.

- I bicycled to work for awhile, but it’s gotten too cold for that now. Lost my only form of exercise right there.

- Still enjoy talking to myself.

“Haha, that is pretty path…wait a minute…”

Objectives for 2012:

- Improve myself as a Business Intelligence developer.

- Finish my Peer Review blog series!

- Get my own site (or at least my own domain name)…

- Learn how to read Japanese.

- Work out regularly. Preferably jump roping again.

Next post will be the 4th in my Peer Review blog series! I think I’ll keep the procrastination down this time around.

“Uh huh.”

Not Just Another Untimely Update

Whoa, and suddenly it’s 2011! So the reason why I haven’t updated the blog in awhile is because I’ve been busy with a couple of things.

“Procrastination being one of them.”

The important one being that I got a new job.

“But not denying the procrastination, I see?”

And if you don’t include the things I’ve done for internships, holiday jobs and nonprofit organizations (as a volunteer), then (jr.) Business Intelligence Developer is my first job. Which is kind of cool. Now, I’ve been ranting about Business Informatics in the past, and now I actually have a good excuse to be blogging about that. Technically, Business Informatics != Business Intelligence, but Business Intelligence definitely does fall under Business Informatics (like many other things).

Which means that Scholarly Communication 2.0 is officially demoted to the status of Pet Project.

“Awwwww”

Having said that, I will definitely finish my “A Proposal To Improve Peer Review: A Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform” blog series before blogging about Business Intelligence. I don’t like leaving things unfinished. More importantly: I like it too much to drop it. It’s not without its kinks and I can’t empirically show that it’s a better way of improving peer review/scholarly communication. Still, based on the research I’ve done and the ideas I’ve put in to tackle the most common obstacles, I believe it’s the right way of going about it. So I’m not going to stop with it anytime soon. I might not be blogging about it as much as I should (after I finish the blog series) until I can find new insights into its feasibility or someone adventurous enough to build it.

So after I wrap that up I’ll be mainly blogging about Business Intelligence. A good topic to start with is what classifies as a great Business Intelligence professional and what I need to do to become one. The actual journey of getting there is probably going to offer a lot of good blogging material, too.

“Any update is better than no update, I guess.”

The primary area of expertise that I’ll be developing in (as a professional) is DWH/ETL. It’s more the technical side of Business Intelligence, using SQL Server/SSIS. But there will also be Business Intelligence Reporting, using Cognos Report Studio (MDX). I will be receiving training in these areas soon from veteran Business Intelligence professionals. And, depending on how I grow with that and the actual work, I might buy a few good books on DWH/ETL to further increase my knowledge and develop additional skills.

And that’s pretty much all I have to say in this update. Oh, speaking of volunteering for nonprofit organizations: I recently became the webmaster of a local Amnesty International group. Currently I don’t have a lot to do, but it’s fun to work on and update a website and think about ways to get people’s attention.

“Because you’ve been so great with that, haven’t ya? Tsk tsk…”

Well, more on that in another blog post. Later.

A Proposal To Improve Peer Review: A Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform (part 3)

This is part 3 of my blog series where I present our proposal/working paper to improve scholarly communication. You can find part 1 here and part 2 here.

Towards Scholarly Communication 2.0: Peer-to-Peer Review & Ranking in Open Access Preprint Repositories is the title of our working paper and can be downloaded for free over at SSRN.

A quick recap of the previous two parts:

In part 1 I’ve talked about the potential of a unified peer review platform to improve the certification function of scholarly communication. The bottleneck, however, is that journal publishers and their editors have neither the time nor the motives to contribute to such a platform systematically, continuously and publicly. Our proposal then shifted from a “unified peer review platform” to a “unified peer-to-peer review platform”. In other words, we’ve focused on designing a peer review model that can work independently of journal publishers (and their editors). This lead to our choice of Open Access preprint repositories as the technical foundation for our model: access to manuscripts eligible for peer reviews and a platform for scholars to gather and share their works.

In part 2 I’ve provided an overview of the functions of the peer-to-peer review model. Specifically it covered seven important activities that journal editors carry out that have to be compensated for in a peer-to-peer review environment. It also explains how participants can remain anonymous while still being rewarded proportionally to their contributions with an impact metric for reviews.

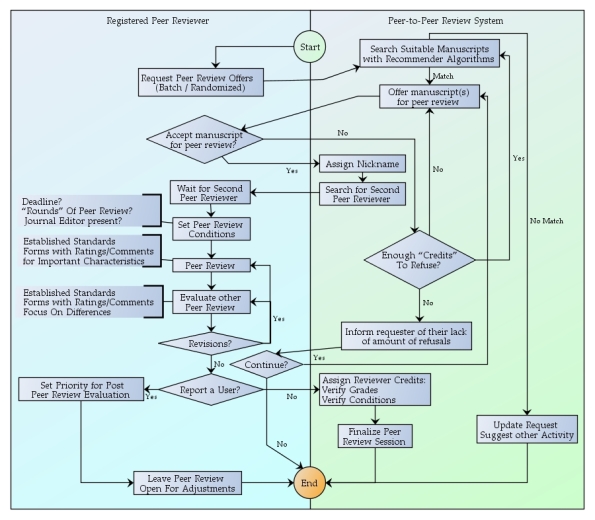

In part 3 of the blog series I’ll focus more on the actual peer-to-peer review process of our model. We explain how we think our proposal can be realized functionally and technically. There will be a lot of quoting from our working paper, since a lot has already been succinctly stated there. I’ll add an original flow chart to make this information easier to digest.

Focusing on the Peer-to-Peer Review Process

This section describes the functions that allow scholars to proficiently peer review manuscripts and evaluate these peer reviews. These activities generate Reviewer Credits and are added to their Reviewer Impact. The peer-to-peer review model borrows heavily from the traditional journal peer review. Since the traditional journal peer review is the most established peer review system, providing similar functionality is a practical step to increase its feasibility.

This activity diagram is divided in what the registered peer reviewer sees and inputs, and the “internal processes” that take place “behind the scenes” but aren’t visible to the users.

The peer-to-peer review process starts when registered scholars make themselves available for (blind) peer review. A manuscript selection system, which will be automated as much as possible, attempts to find and present scholars with suitable manuscripts to choose from. At this stage, scholars are free to turn down any of the peer review offers without facing any penalties (to their Reviewer Impact). There will, however, be a limit to how many times a scholar can reject peer review offers before they’re asked to “replenish” their number of limits with either peer reviews or other important tasks. This measure is to improve the probability of scholars ending up with manuscripts that they can peer review with no conflicts of interests.

Two peer reviewers are required for each manuscript. Each peer reviewer has two primary tasks per peer review session:

- peer review the manuscript;

- peer review the other peer review.

Specifically designed quality assessment instruments, designed around the relevant characteristics of sound manuscripts, are available for these peer review processes. These activities result in two reports per peer reviewer:

- the peer review report of the manuscript;

- the “peer review report” of the peer review of the other peer reviewer.

After the reviews have been exchanged with the authors and the other peer reviewer, the involved parties are provided with the opportunity to discuss the reports. Discussions can be held on a private discussion board that can only be accessed by the respective participants to iron out difficulties. Peer reviewers can review the feedback and optionally revise their reports and their scoring. Like the traditional journal peer review, this setup requires two scholars for the actual peer reviewing which also helps maintain the same level of efficiency and workload.

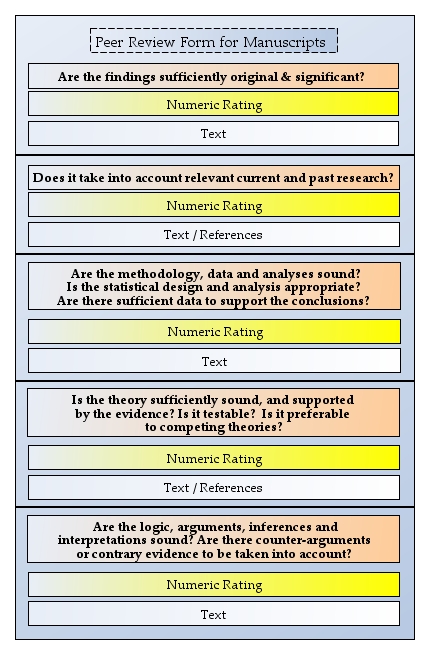

To achieve a high degree of objectivity and efficiency, the structure of the peer reviews has to encourage peer reviewers to comment and score on all the significant characteristics of sound research papers [Brown 2004; Davison, Vreede and Briggs 2005]. Similarly, the model has to provide proper accommodations for peer reviewers to systematically assess the quality of the peer reviews. To improve its feasibility, the design of such accommodations will be based on existing peer review quality assessment instruments [Jefferson, Wager and Davidoff 2002; Landkroon et al. 2006; Van Rooyen, Black and Godlee 1999].

An example of utilizing these instruments is a form with room for ratings and comments for each significant characteristic. Each rating for a manuscript can have a different weight factor, depending on the characteristic, and the scores will accumulate to a total score. The assessments of the peer reviews themselves could be based on similar ratings and a “highlight” tool to support each rating. Each highlighted part of the other peer review report represents something the other peer review lacks or has extra compared to their own peer review report.

Finalizing Peer Review Processes

A peer review process is not finalized until all peer review reports have been signed off by their respective peer reviewers (within their predetermined time limits). Until that point, peer reviews are open for revision as many times as considered appropriate. This allows peer reviewers to engage in a multiple tiered peer review process. The parties involved can decide how many times they are willing to discuss and revise their reports. They can also agree not to discuss or change and only write a review and submit it immediately without seeing the other report until it has been finalized. When there is still a disagreement in the scoring, the notification function can be used to request other peers from reviewing how the evaluations were performed. Using the notification function likely takes a longer time than for the peer reviewers of those respective sessions to discuss and come to a middle way regarding the scoring by themselves, however.

Each peer review assignment is constrained by predetermined time limits. The default time limit for an entire process is, for example, one month after two peer reviewers have accepted the peer review assignment. Authors and peer reviewers can consent to change the default time limit during the acceptance phase. Any reviewer who has not “signed off” by then will have Reviewer Credits extracted until the reviewers of the reports sign off or when the application for a peer review is terminated. This measure is to prevent a process from going on for a far longer time than agreed to beforehand, which is not desirable for any party.

An example of how the termination can work: a termination can happen when no new deadline, agreed by the authors and peer reviewers in question, has been set two weeks after it has passed the original deadline. In the case of termination one or more new peer reviewers will have to be assigned to the peer review session to achieve the minimum of two peer reviews per manuscript. The involved parties can unanimously extend the peer review session as often as they wish, but at a maximum of two weeks for each extension. This provides the authors with the option to cancel a peer review session every two weeks. No Reviewer Credits are assigned with a cancellation.

When authors are not content after having gone through a peer review process, they can leave manuscripts “open” for others peer reviewers to start a new peer review session. The newer peer reviewers will have access to peer review reports of previous sessions, creating an additional layer of accountability. Concerning the consequences of multiple peer review sessions for the same manuscripts; in the traditional system the latest peer reviews, before a manuscript is accepted for publication, are the ones that count. In our peer-to-peer review model, the manuscript score is based on what the peer reviewers of the newest session have assigned to them. This is regardless of whether the scores are higher or lower than the previous manuscript scores.

A possible alternative to this is to let the authors decide which results to attach to the manuscript. A disadvantage of authors selecting which set of grades to use is that it could likely weaken the importance of the earlier peer review sessions. To improve accountability and efficiency, previous reviews are not hidden from any future peer reviewers. The reviews will still count and the peer reviewers who have submitted them keep the Reviewer Credits awarded to them. Regardless of how and which sets of grades are utilized, those chosen grades are to be reflected in the rankings and returned search results.

Consequences of Multiple Peer Review Sessions

By allowing more than one peer review session, rules are needed concerning the impact of the previous raters. Granted, the newest peer reviewers cannot simply change the previous grades of others to “correct” their statistics. There are a couple of options available if the newest peer reviewers agree with the authors regarding the need for their additional peer reviews. If the newest peer reviewers agree that the grades do not accurately reflect the peer review quality of the previous peer reviewers, they can put those reports on notification and add arguments to support that decision.

If any peer reviews are put on notification, the involved parties are first offered another opportunity to settle things between themselves. If that does not result in the notified reports being adjusted or the authors agreeing with the assessments, the option to make the notified report openly accessible to registered peers will be available. If the reported evaluators stand by their reports, allow the other parties to make the reports in question public for more peers to evaluate. Let a larger community of peers decide whether the report is justified or not.

If after a certain amount of time and responses the majority agree that the reporting side is right, the notified case has to have its grading adjusted or even removed entirely. At worst, a ban of the registered scholar in question is issued. If the majority of the peers are not in an agreement, the scholar that reported will be the one being reprimanded by this same group of peers. Notifications through e-mail can be sent to peers in that same field to reduce the time these specific reports are found and evaluated. During this time of “public scrutiny” any Reviewer Credits that were accredited are temporarily removed until there is a conclusion.

Suppose that parties have decided to make their notified case available to a larger community of qualified peers, but little to no attention is given to it. This is not an uncommon scenario in an “open” environment with neither encouragement nor enforcement. If at least one of the peer reviewers insists on having a more satisfying conclusion, an option to ensure peer review sessions are finalized is to allow the model to automatically select one new peer reviewer to “audit” the notified case. This “external peer” can be given the authority to adjust the ratings of the assessment that has been reported or invalidate the “notified” status. To improve the accountability of these “external peers”, their actions themselves must be recorded with the particular manuscript and viable for change themselves by any future peer reviewers of those manuscripts.

Another option is to leave the notified works publicly visible as they are, but have the real identities of the “notifiers” and the “notified” attached to that particular peer review process. These options could be made available after a case has been made public, but has received no result at all after two weeks, making it six weeks after the two peer reviewers have accepted it with the default time limit.

Summary

And that’s it for part 3. This peer-to-peer review process pretty much lays the groundwork for the rest of the activities and procedures. In part 4 of this blog series I’ll talk more about how Reviewer Credits are credited and about a special ranking system for manuscripts based on citation counts. The latter is an idea to simulate the journal impact factor, but with more flexibility to improve the accuracy.

In part 5 I focus on answerability: how can this model encourage/enforce objective and professional peer reviewing from scholars? It’s a very important topic, but one that I can best tackle after presenting how Reviewer Credits are credited.

P.S. yEd – Graph Editor is the tool I use for the graphs in this blog post. It’s pretty handy.

yEd is a powerful diagram editor that can be used to quickly and effectively generate high-quality drawings of diagrams.

yEd is freely available and runs on all major platforms: Windows, Unix/Linux, and Mac OS.

References

- Brown, T. 2004, ‘Peer Review and the acceptance of new scientific ideas’, Sense about Science. Available at: http://www.senseaboutscience.org.uk/pdf/PeerReview.pdf [Last accessed 24 July 2009]

- Davison, R.M., de Vreede, G.J., Briggs, R.O. 2005, ‘On Peer Review Standards For the Information Systems Literature’, Communications of the Association for Information Systems, vol. 16, no. 49, pp. 967-980.

- Jefferson, T., Wager, E., Davidoff, F. 2002, ‘Measuring the quality of editorial peer review’, Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 287, no. 21, pp. 2786-2790.

- Landkroon, A.P., Euser, AM, Veeken, H., Hart, W., Overbeke, A.J.P.M. 2006, ‘Quality assessment of reviewers’ reports using a simple instrument’, Obstetrics And Gynecology, vol. 108, no. 4, pp. 979-985.

- Van Rooyen, S., Black, N., Godlee, F. 1999, ‘Development of the Review Quality Instrument (RQI) for assessing peer reviews of manuscripts’, Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 625-629.

A Proposal To Improve Peer Review: A Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform (part 2)

This is part 2 of my blog series where I present our proposal/working paper to improve scholarly communication through the peer review element. You can find part 1 here.

Towards Scholarly Communication 2.0: Peer-to-Peer Review & Ranking in Open Access Preprint Repositories is the title of our working paper and can be downloaded for free over at SSRN.

A quick recap: In part 1 I’ve presented the opportunities of a unified peer review platform to improve the certification function of scholarly communication. The bottleneck, however, is that journal publishers have no incentives to allow their journal editors to participate to initiate peer reviews and share their peer reviews afterward. Journal editors have neither the time nor the motives to contribute systematically, continuously and publicly. Our proposal then shifted from a “unified peer review platform” to a “unified peer-to-peer review platform”. In other words, we’ve focused on designing a peer review model that can work independently of journal publishers (and their editors). This lead to our choice of Open Access preprint repositories as the technical foundation for our model: access to manuscripts eligible for peer reviews and a platform for scholars to share their works. In this part of the blog series we’ll start exploring the consequences of that shift with…

A General Overview of the Model: Simulating the Journal Editor

Since the journal editor plays a pivotal role in the (journal) peer review process, the peer-to-peer review process needs to compensate for the lack of journal editors to be feasible. In the working paper, we identify seven activities that journal editors carry out with regards to certifying manuscripts. By providing alternatives to execute these activities in a peer-to-peer environment, we’re essentially laying down the functional foundation of our peer-to-peer review model. After that, we can focus on the actual peer-to-peer review process, but that’s for another blog post. Since I’ll present a brief overview of the model here, I’ll also occasionally quote directly from our working paper, since these points are already succinctly phrased there.

The first activity is to screen the manuscripts submitted by authors to determine whether they are worth sending out to their peers for reviews. Manuscripts that they feel are likely not going to be suitable enough to be published in their respective journals are rejected. For our environment, we can provide scholars with the instruments to submit comments and ratings for either the abstract or the entire manuscript. As a screening process, it can be far less thorough but still valuable. By allowing peers to “trust” each others’ ratings, everyday scholars can change into “personal editors” with little additional effort, further improving the screening of interesting/significant papers.

Page 5:

The second activity is to select suitable peer reviewers for the (screened) manuscripts.

There are two elements in this activity. The first element are the qualified scholars for the peer reviews. The second element is the ability to properly match those qualified scholars with the manuscripts that are eligible for peer review. We propose to tackle the first point as follows (page 5):

For the peer-to-peer review environment, qualified scholars can be located in various ways. One way is to integrate the registration database with the author databases of the repositories themselves. Another approach is to grant special authorization to scholarly institutions to manually register their scholars.

The second point, matching qualified scholars with the right manuscripts for peer review, is a lot more difficult. In fact, it’s probably the most difficult thing to achieve with the same effectivity and efficiency. The feasibility of the entire model will largely depend on how well we can achieve this particular process. In the paper we’ll go in greater detail how we think this can be achieved, but for now this will set the direction of the solution that we’re proposing (page 5):

There are several potential approaches to match manuscripts with suitable scholars for peer review. One obvious approach is to let registered scholars choose which manuscripts they wish to peer review. That approach will avoid any issues concerning incompatible expertise between the manuscripts and the peer reviewers. Ensuring a satisfactory level of objectivity will be complicated when scholars can pick whom and what they get to evaluate, however. A more reliable approach is necessary. One such approach is to automate this process by utilizing specialized recommender systems [Adomavicius and Tuzhilin 2005]. Specifically, an automated manuscript/peer reviewer selection system [Basu et al. 2001; Dumais and Nielsen 1992; Dutta 1992; Rodriguez and Bollen 2006; Rodriguez, Bollen and Van de Sompel 2006; Yarowsky and Florian 1999] that matches the peer reviewers’ preferences and expertise with the manuscripts.

“Second” Obligatory Reminder: this is not the complete solution that we propose for selecting suitable peer reviewers for manuscripts with no conflicts of interests in our peer-to-peer environment. We do not think that this process can currently (or even in the nearby future) be fully automated. It is, however, an important element and it will go a long way toward making this entire process less labor intensive. We will cover this important topic more thoroughly later.

The third activity is to act as an intermediate between authors and peer reviewers. Editors serve as an indirect communication channel. An important benefit of these selection and intermediation functions is that peer reviewers can remain anonymous. Anonymity allows them to be more honest about their assessment, as they don’t fear any kind of “retaliation” by the authors for criticizing their manuscripts. Of course, anonymity also means that it’s easier for peer reviewers to criticize a manuscript harshly, justified or not.

Page 6:

The ability to provide scholars with all the instruments they require to peer review anonymously while still being properly credited for it is not a complicated functionality in the digital world. To be completely anonymous to all human parties, but still receive proper credit for every contribution is a unique and significant benefit of a digital scholarly communication system.

To achieve that benefit, the model provides scholars with the option to register with their real identities. They can then opt to carry out activities anonymously under generic “nicknames”. Those activities are then scrutinized and quantified. Their contributions quantified are their Reviewer Impacts. After every valuable contribution, a scholar’s Reviewer Impact is appropriately adjusted and then attached to their real identity. Through this approach, every scholar is responsible for what they do, but it will be their Reviewer Impact that essentially represents the quality of their actions.

The fourth activity is to verify the quality of the manuscripts, where the journal editor essentially acts as a peer reviewer. For this matter, specific accommodations for proper peer reviewing are accounted for in this model. These accommodations can be forms that include the relevant manuscript and peer review criteria to support the peer reviewers in peer reviewing and evaluating each others’ peer reviews properly.

Page 6:

The fifth activity is to verify the quality of the peer reviews; acting as a peer reviewer of the peer reviewers. With or without editors, but especially without, the model provides instruments for peer reviewers to assess the quality of the peer review reports of their peers. As mentioned in the previous activity, these instruments will be forms with the relevant characteristics of proper peer reviews for scholars to provide their feedback with.

Page 6:

The sixth activity is to decide whether to approve the peer reviewed manuscripts for publication, approve after revision or an outright rejection. The peer-to-peer review model is focused on quality control for the sake of “grading” a manuscript and properly crediting peer reviewers for their work. Whether the manuscripts will then be picked up for publication, grant funding, academic ranking or simply remain in the respective repository as a peer reviewed research article is not a focus point. For feasibility purposes, the important thing is to accommodate these different options. Examples of these accommodations are publicly accessible rankings of papers based on their citation counts and based on the grades by peer reviewers.

Page 7:

The seventh activity is to determine the visibility of publications, including the layout of the magazine and the time of publication. A key objective of this model is to offer scholars practical rewards to encourage regular, valuable contributions. With the output and proficiency of the peer reviewers quantified in Reviewer Impact, there are ways to rank them systematically, based on their peer review performance. For a more direct approach, there is a peer reviewer ranking with the names and their Reviewer Impact publicly visible. Indirectly, the system can rank their preprints and improve their visibility by positioning them higher on returned search queries.

Since I feel bad about quoting so much verbatim from our paper for this blog post, here is an original image to somewhat reflect what is stated here (and in the paper) for additional clarity.

Summary Part 2

Our peer-to-peer review model allows scholars to peer review anonymously and credits them for their work. Established quality assessments instruments are included to improve the effectivity and efficiency of these assessments. In the next part (of the paper), we present the workings of the actual peer-to-peer review process in greater detail. We also focus on measures to achieve accountability, efficiency and effectivity with this peer-to-peer review process.

References

- Adomavicius, G., Tuzhilin, A. 2005, ‘Toward the Next Generation of Recommender Systems: A Survey of the State-of-the-Art and Possible Extensions’, IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 734-749.

- Basu, C., Hirsh, H., Cohen, W.W., Nevill-Manning, C. 2001, ‘Technical Paper Recommendation: A Study in Combining Multiple Information Sources’, Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, vol. 14, pp. 231-252.

- Dumais, S.T., Nielsen, J. 1992, ‘Automating the Assignment of Submitted Manuscripts to Reviewers’, in Proceedings of the 15th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Copenhagen, Denmark, pp. 233-244.

- Dutta, A. 1992, ‘A deductive database for automatic referee selection’, Information & Management, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 371-381.

- Rodriguez, M.A., Bollen, J. 2006, ‘An Algorithm to Determine Peer-Reviewers’, Working Paper. Retrieved June 25, 2008, from http://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0605112v1.

- Rodriguez, M.A., Bollen, J., Van de Sompel, H. 2006, ‘The convergence of digital libraries and the peer-review process’, Journal of Information Science, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 149-159.

- Yarowsky, D., Florian, R. 1999, ‘Taking the load off the conference chairs: towards a digital paper-routing assistant’, in Proceedings of the 1999 Joint SIGDAT Conference on Empirical Methods in NLP and Very-Large Corpora, University of Maryland, Maryland.

Defending the Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform Proposal Part 3

This is part 3 of my defense against David Crotty’s (additional) critique. The topic of our exchange is our working paper. Part 1 of our exchange is here (a different style of blog title there, though. I apologize for the confusion). Part 2 is here.

If you want to skip this and just read about our proposed model from the beginning, you can either go to the first part of my blog series that summarizes our proposed model (and wait for updates) or read our paper in its entirety right here.

Citation: you can imagine other factors being added in, but from my recall, citation was the factor that was mentioned over and over again as being used to score a reviewer’s performance.

Not quite. The paper citation count is actually “just” another element of the Reviewer Impact. The grades for the peer reviews by the other peer reviewers are far more important. We didn’t design nor intended for the paper citation count to be relatively more influential for the Reviewer Impact of scholars.

I agree that citation is an incredibly important metric, but it’s a flawed one as well. It’s impossible to separate out a citation in a subsequent paper that lauds an earlier discovery versus one that proves it to be untrue. Fraudulent and incorrect papers get cited lots.

No disagreements here. As mentioned in part 2 (and in the paper, of course): the paper citation count does have a substantial role in determining the rankings of the eprints by default. But that’s not really any different from how it is utilized now. I wonder how feasible attaching a +/- value to citations will be for the model?

Citation is a very slow metric as well, as you note in your proposal. If Reviewer Impact is indeed important to a career, it may not fit into the necessary timeline for someone up for tenure or funding.

Reviewer Impact can help one’s career a bit, indirectly, by improving the visibility of one’s papers. The actual effect of citations is rather modest in this context. A high Reviewer Impact will do very little, if anything at all, for authors who have papers that aren’t interesting to scholars to begin with. A high Reviewer Impact will likely do something for authors with papers that are interesting to scholars to begin with.

And citation is certainly an area where one could game the system, by deliberately citing all of the papers one reviewed. If the Reviewer Impact score is somehow decided to be important, you could choose papers relevant to your own work, give them a good review then cite them, thus pumping up your own score for judging science.

The Reviewer Impact is not designed nor was it ever intended to be significantly influenced by the paper citation count. Which is why I consider your scenario to be rather farfetched. However, you are correct that it is still a factor and it is still exploitable so I should take it seriously. So thank you for bringing up this point. I’ve spent a good part of an afternoon thinking of ways to tackle this issue.

Here’s one pretty surefire way to tackle the issue: if the Reviewer Impact becomes so important to scholars that they are willing to “unjustly” increase the citation count of the papers that they have reviewed and scored favorably (on “significance/impact”) just to gain that little bit of advantage (from one element of their peer reviews), I think it’s safe to assume that by then the peer-to-peer review model is very established. Likely established enough that we no longer need the “personal” incentives to encourage scholars to participate. Thus we remove the incentives in favor of improving the effectivity and efficiency of all our scholarly communication functions, while at the same time eliminating many of the personal motives for scholars to exploit the system. I’d really rather not do this unless there’s absolutely no other way of preventing people from exploiting the paper citation count and possibly other exploits, though.

A more technologically challenging approach is to develop a function that can automatically track which authors have cited which papers. And then track whether they have peer reviewed those papers (positively), but without providing the names of the actual papers to ensure the identities of the peer reviewers are not exposed. To allow a higher degree of accountability, this information can then be publicly displayed, e.g.: “This author has a total of x citations divided over x papers that he/she has also peer reviewed (and rated positively)”. After deciding what are unreasonable levels of such incidents taking place, we can either nullify the impact this measure has on their Reviewer Impact. Of course, they could avoid this measure by having “friends” cite those papers for them so they’re not directly connected.

The easiest solution is to simply remove the paper citation count as an element that can influence a scholar’s Reviewer Impact. They must still assess the significance of a paper, but only to the benefit of the other scholars, not themselves. If we were to use this solution, we must think of another way to reflect a peer reviewer’s ability to accurately assess the significance of a paper in their Reviewer Impact. After all, it is a valuable skill and reflects the understanding the scholars have of their disciplines. Perhaps we should have the model and these specific elements depend (more) on the expert reviews of registered scholars. For example, based on just the abstract, introduction, discussion and conclusion of a paper, provide scholars with the means to rate, comment and provide additional evidence for the significance of the reviewed paper. They have to be qualified to determine this for the research topic of the paper. Since the focus for them should only be on the papers they find significant and can say something positive about, their real identity will also be attached to it.

Another example of a place for gaming is in reviewing the other reviewer on your paper. As I understand it, there are a certain number of “reviewer credits” given for each peer review session. If those are divided among the paper’s reviewers based on their performance, isn’t there an advantage in always ranking the other reviewer poorly so you garner more of the credits?

Authors and peer reviewers must unanimously consent to “finalize” a peer review session. They will have access to the peer reviews of the other peer reviewers before they receive the option to end that particular peer review session. If this doesn’t lead to a satisfying result the assessments can be made publicly visible. This will consequently provide a larger group of peers the opportunity to share their thoughts and finalize it for them. The peer reviewers will receive the opportunity to adjust their assessments before that can happen. Either way, no Reviewer Credits will be credited until peer review sessions are finalized.

Delays: one month is a lot longer than my current employer gives reviewers (2 weeks).

The 1 month is just an example and can be changed. I think this will also vary per discipline.

Furthermore, as you note, the time limit can be changed by the reviewers.

Oops, that’s supposed to be a consensus of authors and peer reviewers. We got it right with the “new deadlines”, but not with the default time limits. Good catch! And while we’re at it, it’s probably a good idea to set the maximum extension limit to 2 weeks every time. This way authors (and peer reviewers) receive two weeks every time to consider if the peer review sessions are going somewhere or if they should just cancel them.

If a paper gets a bad reviewer who unfairly trashes it, should that paper be permanently tarnished by having that review read by every subsequent reviewer? Wouldn’t it be better if they gave the paper a fair chance, a blank slate? Clearly I’m not alone in thinking this, as the uptake levels for systems like the Neuroscience Peer Review Consortium are microscopic (1-2% of authors).

Better for the authors, yes. And what if the reviews are fair and the authors unfair in #1. their treatment of the reviews and #2. their assessment of their manuscripts? On what basis do the authors/papers deserve another “fair” chance then? Aren’t you the one overly relying on authors to be completely truthful and objective about their own manuscripts now?

This seems to be an interesting contradiction: if editors are really as valuable as we think they are when it comes to selecting the best peer reviewers, then shouldn’t we also expect that, in general, peer reviewers will objectively, proficiently and constructively review manuscripts? What is the problem then with sharing the reviews with other valuable journal editors who will choose the best peer reviewers? Other than the competitive reasons? If the “consensus” is that these peer reviews shouldn’t be shared with other journal editors and their selected peer reviewers, doesn’t that imply that something is wrong with the ability of journal editors and their selected peer reviewers to carry out their tasks in an objective, constructive and proficient manner? And that we should encourage a higher degree of accountability, both for the authors and for the peer reviewers?

One good reason I can think of why peer reviews shouldn’t be shared, with respect to improving scholarly communication in general, is because the authors have revised the manuscripts and the peer reviews have become irrelevant. Which means that sharing them would be a waste of time for the new peer reviewers. This can somewhat be addressed with a “Track Changes” function that can neatly display the changes of the manuscripts in relation to the specific points of feedback by the corresponding peer reviewers.

Additional work: there’s a huge difference between reading through the other reviewer comments on a paper and in writing up and doing a formal review of the quality of their work. If one is to take such a task seriously, then it’s a timesink.

I think it’ll depend on the design and use of the quality assessment instruments. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a big write up of the other peer review report. It could be based on providing ratings for each of the important characteristics of a good peer review and a “highlight” tool to support each rating. Each highlighted part of the other peer review represents something the other peer review lacks or has extra compared to their own peer review report. The entire process does not have to be complicated or time consuming to still be constructive.

There seems to be a whole raft of negotiations involved and extra duties, extra rounds of review. The proposal itself is highly complicated, filled with all sorts of if/than sorts of contingencies. You’ve certainly put a lot of thought into it, but it’s way too complicated, too hard to explain to the participants.

I expect that the model will be easier to explain once it’s out of the design/brainstorming phase. The current phase is about presenting as many solutions as possible to address every single significant issue that we can think of. If the model wasn’t so “complex”, I’d likely have a lot harder time replying to your criticism, for example. If we can actually build the tools, it’ll be easier for them to just use the tools, rather than read about them.

The ideal improvement to the system would be a streamlining, not an adding in more tasks, more negotiation, more hoops through which one must jump. Time is the most valuable commodity that most scientists are having to ration. Saving time and effort should be a major focus of any improved system.

First of all, the proposed model is designed to reduce the time and effort of scientists, among other things. Secondly, a lot of critics disregard new models for a lack of personal incentives. Pretty much like what you’ve been doing, and I’d like to think this is one of the few ideas that has actually focused on providing said personal incentives to participants. And it’s a bit difficult to provide personal incentives, whatever they are, without a way to assess the exact contribution of participants so one can reward them more appropriately. And one thing led to another and this proposed model is the result of just wanting to make scholarly communication better and still provide personal incentives.

I do think you have some interesting ideas here, and I look forward to seeing future iterations.

Thanks. Some of your feedback has helped me come up with some new ideas to improve the model a bit.

Defending the Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform Proposal Part 2

I really hate writing long comments in (most) comment sections, because the readability is usually terrible. So I’m going to spend another blog post to reply to David Crotty’s additional critique. The topic of our exchange is our working paper. Part 1 of our exchange is here (a different style of blog title there, though. I apologize for the confusion). This is part 2 and there will be a part 3, because there are too many things in the critique that require more detailed responses to fit in one blog post, unfortunately.

On a related note: I can’t shake the feeling that I’m totally destroying the proper flow of presenting our model with these exchanges, though. We’re jumping all over the place with this. If you want to skip this and just read from the beginning, you can either go to the first part of my blog series that summarizes our proposed model (and wait for updates) or read our paper in its entirety right here.

The point there was to talk about the futility of social reputation scoring systems as motivators for participation in a professional market. That’s where the question “who cares” is an important one.

Yes, I know what your point is. And I’m saying that just because there haven’t been many success stories, if any, it doesn’t mean it’s impossible. It just means that it is, at best, very difficult and the odds are very high that our model isn’t feasible. Consider me fully aware of this reality. On that note, I thank you for investing time and effort into reading our working paper and providing feedback for it. I truly appreciate that (well, not necessarily for your first entry, but certainly for this one).

No one questions the desire to improve the peer review process, improve science publishing, improve communication and speed progress. If your system accomplishes those sorts of things, then isn’t that motivation enough?

It sure is, but what if we don’t see a way of doing that unless we can somehow measure the contribution of scholars in the role of peer reviewer and provide them with “personal” incentives proportionally? To you, a scoring system may just be a useless shiny number generator, but for us it’s an integral part of getting this model to function properly and realize the benefits that come with it. Actually, if we can motivate enough scholars to peer review with our approach (or similar methods) and verify that such approaches truly improve scholarly communication in general, I’m not ruling out the idea of removing these “personal” incentives. But to me, they are more than just personal incentives; I genuinely believe these incentives can additional provide important value to scholars, such as an indirect “rating” of manuscripts (more on this later).

Adding a scoring system does not seem to be a big motivator, particularly, as noted in the blog, because it’s irrelevant outside of your system.

Our “system” is actually the entire environment of Open Access preprint repositories including additional databases/archives with (peer-to-)peer reviews of those preprints. It’s relevant to all the scholars who are interested in platforms with scrutinized research literature. That’s not a small area of relevancy.

If I’m up for tenure and I haven’t published any papers or secured any grants, will having a good Reviewer Impact score make any difference to my institution? If I’m a grant officer for the American Heart Association, I’m looking to fund researchers who can come up with results that will help cure disease, not researchers who are good at interpreting the work of other researchers or who are popular in the community. Why would I care about a grant applicant’s Reviewer Impact score?

I noticed I’ve missed this part in your original blog post as well. I’m going to skip commenting on this right now because I don’t think you fully understand our intentions with Reviewer Impact as an incentive for scholars to peer review. Instead, I’ll talk a little bit more about that in reply to your following statements:

For any system to be adopted, it has to have clear utility and superiority on its own. An artificial ranking system does not add any motivation for participation. The one benefit offered by your Reviewer Impact score is more visibility for one’s own papers.

Actually, that’s not the only benefit. The Reviewer Impact’s most significant role is to help with enforcing accountability, actually. And we’re hoping that a more accountable system leads to peer reviews of a higher quality, which leads to more incentives for scholars. Anyway…

That seems to be the opposite of what you’d want out of any paper filtering system. You want to highlight the best papers, the most meaningful results, not the papers from the best reviewers. If a scientist does spectacular work but is a bad reviewer, that work will be buried by your system in favor of mediocre work by a good reviewer.

A legitimate concern. In fact, it’s so legitimate that we’ve thought of it as well. Page 18:

When scholars are searching and browsing for manuscripts, the order of the peer review offers of the manuscripts are prioritized based on relevance. However, if the degree of suitability and relevance of the manuscripts is largely the same, the manuscripts of the scholars with a higher Reviewer Impact will be listed higher on search results, browse results and their lists of peer review offers.

So while I think I did say papers in the last reply to you, I meant “manuscripts” or “preprints”. I agree absolutely that the good papers should be at the top of the heap, but the rankings of preprints are (more) fair game. Once someone can establish the quality of the preprints, this personal incentive is going to be far less effective.

Page 18 again:

The paper citation count alone is widely considered as one of the best, if not the best, quality indicator of a paper that scholars have. It is therefore more reasonable to attach far less weight to the Reviewer Impact in determining the priority, if at all, and more weight to the other quality indicators when it comes to postprints.

And page 19:

In order to avoid such conflicts, we could apply the following conditions: the priority level for preprints in search and browse results are for 50% determined by the Reviewer Impact of the authors. 30% is based on more established quality indicators such as paper citation counts. The remaining 20% is based on the “informal” manuscript screenings and other quality indicators. For postprints, 60% is based on quality indicators such as paper citation counts and the peer review grades. 20% is based on their Reviewer Impact, and the remaining 20% is based on the informal manuscript screenings and other quality indicators. These conditions can be revaluated once they have been put in effect and more insight is available on their effectiveness. For example, if there is evidence that the Reviewer Impact of scholars is more accurate in reflecting the quality of the manuscripts of the respective authors than previously assumed.

That said, I’m happy to expand my comments on your proposal. As a working paper, it deserves scrutiny and hopefully constructive criticism to improve the proposal.

Thanks.

I call the automated selection program “magical” because it does not exist, and I don’t think it’s technologically capable of existing, at least if it’s expected to perform as well as the current editor-driven system.

A legitimate concern. As I mentioned before, the effectiveness of our manuscript selection function and the efficiency (with regards to time and effort) of peer reviewing the peer reviews are the biggest hurdles for our proposal. But even if our manuscript selection function cannot be optimized to eliminate the same number of conflicts of interests as journal editors do now, that doesn’t actually mean that the total amount of peer reviews through our method will be relatively of lesser quality compared to the total amount of peer reviews through the traditional journal peer review. In exchange for a lack of journal editors, the system does provide a far higher level of (public) accountability. Even journal editors cannot track the degree of professionalism scholars exert (for peer reviewing). That is possible in a unified (peer-to-)peer review system.

Your conflict of interest prevention system relies entirely on reviewers being completely fair and honest.

No, this is actually not accurate. One suggestion we have to improve this conflict of interest prevention system is to have scholars publicly “declare” that there is no conflict of interests. Some excerpts from page 15:

Furthermore, scholars should be given the opportunity and encouragement to mark both manuscripts and papers for which they are “Proficient” to peer review. If this statement is checked, additional statements are presented, such as the “No conflict of interest” statement and whether the scholars are “Interested”, “Very Interested” or “Not Interested” in peer reviewing the respective manuscripts and papers.

After a manuscript has a certain amount of such “compatibility” statements checked by a number of scholars, a short overview with the titles and abstracts of the respective manuscripts can be added to the real profile pages of these scholars. This allows for a way to validate the accuracy of their claims of proficiency and objectiveness.

So we see this as a method to connect manuscripts with scholars without giving away the identities of the peer reviewers. Which means that…

One of the common complaints about the current system is that reviewers with conflicts deliberately delay, or spike a qualified publication. If those reviewers are so unethical that they’re willing to accept a review request from an editor, despite knowing their conflicts, why do you think they’d recuse themselves in your system?

…our proposed system allows practically anybody to verify (and call to attention) potential conflicts of interests. This allows for a higher degree of accountability and provides the means to stop “repeat offenders”. With the traditional publishing system, this is extremely difficult to achieve, if not impossible. Of course, efficiency is a legitimate concern even if we can enforce standards to minimize the “additional” workload. Again, we certainly don’t deny this is going to take some serious effort to get it as good as with real journal editors, if at all possible.

Isn’t landing a big grant or being the first to publish a big result going to be more important to them then scoring higher on an artificial metric?

Absolutely. But I think what you’re forgetting is that we’re dealing with OA preprints here. Which is both a strength and a weakness. The “strength” is that the part about “stalling a publication” is actually less meaningful in “our” OA preprint environment than in the current scholarly publishing environment. Granted, “ruining” a review/manuscript and delaying a proper “grading” of the preprint is still going to be detrimental to the authors of those preprints. And a bigger “weakness” is that by limiting ourselves to just being able to scrutinize OA preprints, we can never truly compensate for an important service that journal publishers provide: preventing manuscripts from being publicly accessible until it’s been accepted (after revisions, optionally) for publication i.e. “closed” peer review, if you will.

Again, with the ability to confirm and track such offenses globally, we can discourage such incidents from happening (again) better than the current system can, in theory. And I don’t think we should just disregard the potential of the other measures that we have in mind (and written about) to improve this system. But I definitely can see how optimizing this function is going to take the most time. I’m actually secretly hoping that experts of recommendation systems and encryption can give us a piece of their minds on how to best optimize this process through automation and/or allowing people to manually verify which papers scholars have tagged “no conflict of interests” without revealing their identities.

But there’s much more to selecting good reviewers than just avoiding conflicts of interest. Your system relies on reviewers accurately portraying their own level of expertise and accurately selecting only papers that they are qualified to review. One of the other big complaints about the current system is when reviewers don’t have the correct understanding of a field or a technique to do a fair review. A skilled editor finds the right reviewers for a paper, not just random people who are in the same field.

On average, journal editors know enough about the manuscripts and the scholars to estimate whether scholars are capable of properly reviewing it better than the scholars themselves? I find that quite difficult to believe. And scholars certainly don’t have the incentive to risk that in our system. Because all their peer reviews get evaluated systematically. And depending on how they’ve done their job (with very high or very low scores for peer reviews), their reviews could be partly made public.

When an editor fails to do their job properly, you get unqualified reviewers. In your system, this would be massively multiplied as there’s a seemingly random selection of who would be invited to review once you get into a particular field.

This depends on how effective the manuscript selection function will work. And I don’t expect the incompetency of scholars to determine whether they can properly review manuscripts to be that big of an issue, to be totally honest. The stories that I’ve heard are usually the other way around: scholars complaining about journal editors repeatedly sending them manuscripts that are way outside of their expertise, simply because the journal editors don’t have anybody else or part of their stressful routine to get as many peer reviews as quickly as they can. The scholars who cave and do the peer reviews do so because #1. it’s not their responsibility if the peer reviews are of low quality since it’s the journal editors who asked them to do that and, more importantly: #2. they feel they can still contribute to improving the manuscripts, even if it’s not their (main) expertise. And they realize their (weaker) contribution could very well be the only thing these manuscripts will have (before they either get rejected or accepted for publication). And something is better than nothing.

With our system, we’re basically saying: “We’re giving you the option to choose now, ladies and gentlemen. So make sure you get it right, because there’s nobody but yourself to blame if you do a poor job of it. And that doesn’t help you and it doesn’t help the authors that you’re trying to help”. Optionally, we could provide them with the opportunity to simply “screen” (“light” peer review) instead of a “real” review if they feel they have something to contribute to the manuscript, but not fully confident that they can do a good job of it.

Your system seems to have a mechanism built in where a reviewer can only reject a limited amount of peer review offers. After that, he must peer review manuscripts to remain part of the system. That puts pressure on reviewers to accept papers where they may not be qualified.

A fair point. To reduce the impact of this issue, scholars can earn the right to refuse to do peer reviews with activities that require far less time and effort. From “screening” papers to validating the no conflict statements of authors and other useful but less time consuming activities. Page 17:

The third measure is a limit system: a mechanism that enforces a limited amount of times a scholar can perform an activity. An example of such an activity is rejecting a batch of peer review offers. While rejecting manuscripts they do not wish to peer review is acceptable, they cannot reject unlimitedly. They have to peer review or screen manuscripts to regain the option again to reject again.

Still, I imagine the solutions should probably be better. It definitely is food for thought.

Expertise is not democratically distributed. You want papers reviewed by the most qualified reviewers possible, not just someone who saw the title and abstract and thought it might be interesting or because they ran out of rejection opportunities allowed by the system.

All fair points, but as I’ve already commented on them earlier in this reply, I’m going to skip this. In fact, I think this is a good place to end part 2 of my defense. Part 3 coming soon…

A Proposal To Improve Peer Review: A Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform (part 1.5)

Late again. So as I was working on part 2 of this blog series where I present our proposal to improve scholarly communication through the peer review element….I came across this rather scathing review of our proposal by David Crotty.

Since I don’t see the point of working on part 2 while someone has criticized some elements of our proposal, I’m going to take a short break and respond to the criticism first.

First things first, my co-author of our working paper no longer works at Erasmus University Rotterdam. He hasn’t updated his information yet. As for me, I currently don’t have any affiliations (relevant to this working paper anyway). So that’s that. I wouldn’t exactly classify myself as mysterious, as I do have a LinkedIn page where I’ve listed my educational background. But let’s focus on the actual comments.

Their system is designed to begin in open access preprint repositories and then potentially spread into use in traditional journals.

The design should, by default, allow journal publishers/editors to take advantage of the system. But that’s pretty much it. This part doesn’t change at all whether the peer-to-peer review model grows or not.

The proposal is full of gaping holes, including a need for a magical automated mechanism that will somehow select qualified reviewers for papers while eliminating conflicts of interest,

Okay. First of all, I don’t consider the idea of a recommendation system that can match manuscripts with suitable peer reviewers as magical. Now, in the Discussion & Conclusion section of our paper we go over the potential strengths and weaknesses of our peer-to-peer review model. In the “Potential Weaknesses” section of it, we’ve stated the following:

A key requirement of the peer-to-peer review model is that the automated manuscript assignment system has to be effective. Since it is essentially a type of recommendation algorithm, it should be technically and functionally feasible to find suitable manuscripts for scholars available for peer review. We identify two issues that remain for now. The first is how to verify whether there is a conflict of interest without making the real identities public. The ability to verify this would improve the answerability of this model significantly. Technically and functionally, filtering certain matches should be feasible, but it would significantly rely on the information that scholars provide. Perhaps allowing authors to indicate manually which authors (edit: scholars is probably a better term to use here) they do not want for peer review might help address this issue. The manual element can be done anonymously, making it only accessible to the automated manuscript selection algorithms. Ideally, we would be able to rely on the automated selection algorithms for this issue as much as possible. Creating a system that can compare paper abstracts, keywords, scholarly affiliations and future research projects to determine whether there is reason to believe there is a conflict of interest is a critical success factor.

To imply that we completely (and magically!) depend on the manuscript selection element, including the ability to find and reject matches with a conflict of interests, to be fully automated and working perfectly is highly inaccurate. In fact, on page 15, in the “On Peer-to-Peer Answerability” section of our paper, we’ve spent 5 paragraphs on addressing this exact issue, with the second paragraph starting with the following:

Manual approaches should additionally be implemented in the event the recommendation algorithms are unable to detect conflicts of interests. For example, scholars can manually prevent certain scholars from peer reviewing their manuscripts. The number of scholars they can prevent from peer reviewing can be based on the total number of suitable scholars. Furthermore, scholars should be given the opportunity and encouragement to mark both manuscripts and papers for which they are “Proficient” to peer review. If this statement is checked, additional statements are presented, such as the “No conflict of interest” statement and whether the scholars are “Interested”, “Very Interested” or “Not Interested” in peer reviewing the respective manuscripts and papers.

(SNIP: To the next paragraph)

After a manuscript has a certain amount of such “compatibility” statements checked by a number of scholars, a short overview with the titles and abstracts of the respective manuscripts can be added to the real profile pages of these scholars.

The rest you can read for yourself. I won’t do it justice unless I quote the entire thing, and I still got other things to handle in this post. One can certainly question how efficient this model can relatively be with these manual measures (an issue that we’ve also acknowledged and discussed), but to suggest a magical reliance on automating manuscript selections is highly inaccurate.

an over-reliance on citation as the only metric for measuring impact,

Not entirely sure what he’s referring to here. It’s true that we consider the paper citation count an important factor in determining the impact of a paper. And? I can imagine the number of views, downloads, ratings, comments, blog posts and such to be significant as well in determining the impact of a paper. Actually, we have factored in comments and ratings as something that can influence the impact of a manuscript. I’m sure we can consider the others as well later.

and a wide set of means that one could readily use to game the system.

Well, we’ve spent a lot of the paper addressing such issues. Did we identify all exploits? I doubt it. Did we create perfect measures to close the potential exploits? I doubt that. I’d like to think that at the design phase, which is where we are, we can (openly) discuss such issues. I, for one, am very interested in hearing about these ‘means that one could readily use to game the system’.

The proposal doesn’t seem to solve any of the noted problems with traditional peer-review

Solved is a big word. I think our message has been to try and “improve on the current situation”. Few to no incentives, for one. Accountability the other. Insight on the peer review quality (relatively). A higher utility of a single peer review by making it accessible to the relevant parties, such as other journals and peer reviewers of the same manuscript etc.

as it seems just as open to as much bias and subjectivity as what we have now.

Well, we do provide tools that allow scholars to at least track and (publicly) call out such offenses, in very extreme cases. In other cases they will simply not have their work “count” towards their “Reviewer Impact”, which is publicly visible. How is that as open as what we have now?

It’s filled with potential waste and delays as reviewers can apparently endlessly stall the process

What? No. Page 8 and 9:

Each peer review assignment is constrained by predetermined time limits. The default time limit for an entire process is one month after two peer reviewers have accepted the peer review assignment. Peer reviewers can agree to change the default time limit during the acceptance phase. Any reviewer who has not “signed off” by then will have Reviewer Credits extracted until the reviewers of the reports sign off or when the application for a peer review is terminated. This measure is to prevent a process going on for a far longer time than agreed to beforehand, which is not desirable for any party. An example of how the termination can work: a termination can happen when no new deadline, agreed by the authors and peer reviewers in question, has been set two weeks after it has passed the original deadline. In the case of termination one or more peer reviewers will have to be assigned to the peer review session to achieve the minimum of two peer reviews per manuscript.

Not exactly what I’d call the ability to stall endlessly.

and authors can repeatedly demand new reviews if they’re unhappy with the ones they’ve received.

Like how they can do now? Actually, we have something a little different in mind. See page 9:

When authors are not content after having gone through a peer review process, they can leave manuscripts “open” for others peer reviewers to start a new peer review session. The newer peer reviewers will have access to peer review reports of previous sessions, creating an additional layer of accountability. Concerning the consequences of multiple peer review sessions for the same manuscripts; in the traditional system the latest peer reviews before a manuscript is accepted for publication are the ones that count. In our peer-to-peer review model, the manuscript score is based on what the peer reviewers of the newest session have assigned to them. This is regardless of whether the scores are higher or lower than the previous manuscript scores. A possible alternative to this is to let the authors decide which results to attach to the manuscript rating. A disadvantage of authors selecting which set of grades to use is that it could likely weaken the importance of the earlier peer review sessions. To improve accountability and efficiency, previous reviews are not hidden from any future peer reviewers. The reviews will still count and the peer reviewers who have submitted them maintain the Reviewer Credits awarded to them. Regardless of how and which sets of grades are utilized, those specific grades are to be reflected in the rankings and returned search results.

So, yes, authors can demand new reviews if they’re unhappy with the ones they’ve received. And scholars can see how many times they’ve done this already based on the grades (and sometimes more, depending on the grades) of the existing peer reviews of those manuscripts and decide for themselves whether it’s worth their time to peer review them again. Again, you can question the effectiveness of this added level of accountability, but you cannot say authors can “abuse” the concept of requesting peer reviews as many times as they want. They can’t, and certainly not compared to what they already can and generally do with the current publishing system. Also, the section Crediting Reviewer Impact (which starts at page 11) covers additional “penalties” of authors repeatedly accepting new peer reviews.

Reviewers are asked to do a tremendous amount of additional work beyond their current responsibilities, including reviewing the reviews of other reviewers, and taking on jobs normally done by editors. If one of the problems of the current system is the difficulty in finding reviewers with time to do a thorough job, then massively increasing that workload is not a solution.

A legitimate concern. But here’s the thing, we’re not sure this is going to be true. Sure, we ask peer reviewers to additionally evaluate and score the peer reviews of the others. We’ll classify that as a chore. Not entirely substantiated, because we’ve more than once heard the sentiment shared that scholars actually enjoy having access to the other peer reviews of the manuscripts that they themselves have peer reviewed just out of curiosity, or to learn something from it. And are they not evaluating the other peer reviews by doing that? We’re just proposing to provide scholars who want to do that with the tools to do so effectively. But fine, we’ll consider that a chore.

But what if we achieve our intended objectives? What if by doing this the average quality of a peer review(er) goes up? What if the average number of peer reviews for manuscripts go down (because of the instruments that can hold peer reviewers and authors alike more accountable for untimely/low quality work)? And if you have to peer review a manuscript that has been peer reviewed before (but hasn’t been revised), what if you can save time by having access to previous peer reviews? And what if your own manuscripts receive greater odds of being noticed, read, reviewed and cited more often by peer reviewing well (more on this later, or you can just read it in the working paper)? A more efficient allocation (with a global platform) of the available peer reviewers, peer reviews, authors and manuscripts? Have a more objective understanding of (the impact of) your peer review proficiency (relatively to other scholars)? Open Access to scrutinized research literature? Would it still just be a tremendous waste of your time? Or may the benefits actually be worth it? Focusing on just the “chores” without pondering over the potential benefits, both perspectives which we’ve written extensively about, is not a very accurate way of evaluating proposals IMO.

There’s a reason that editors are paid to do their jobs — it’s because scientists don’t want to spend their time doing those things. Scientists are more interested in doing actual research.

And they can do that better when they don’t have to keep on peer reviewing (unrevised) manuscripts that have already been peer reviewed. And when they can have more access to scrutinized research literature.

Like the PubCred proposal, it fails to address the uneven availability of expertise, and assumes all reviewers are equally qualified.

Actually, the whole point of creating a metric for peer review proficiency is to more objectively measure the differences in peer review proficiency among scholars. And by providing them with the instruments to do so systematically, I’d like to think that we can get that kind of information. As for the former issue, I’m not entirely sure what he means. Scholars aren’t being punished for not peer reviewing. They can still submit their papers, and if they’re interesting enough then surely some scholars will want to peer review them, which they can with no penalties.

Also like PubCred, the authors’ suggestions for paying for the system seem unrealistic. In this case, they’re suggesting a subscription model, which seems to argue against the very open access nature of the repositories themselves, limiting functionality and access to tools for those unwilling to pay.

The nature of Open Access preprint repositories is to provide access to preprints. That doesn’t change at all. Everybody can still submit and access preprints in OA preprint repositories. What they might want to be paying for is more advanced search instruments for peer-to-peer reviewed manuscripts (“postprints”). What we propose here is something that can no longer be classified as an “open access repository”. It’s a peer-to-peer review model with an own database for peer reviews and possibly an own database for revised papers, if the repositories “providing” manuscripts can’t accommodate for that, providing open access to scrutinized preprints (“postprints”). Paying for the scrutiny of manuscripts doesn’t go against the nature of scholarly communication, surely.

The authors spend several pages going into fetishistic detail about every aspect of the measurement, but just as in the proposed Scientific Reputation Ranking program suggested in The Scientist, they fail to answer key questions:

Who cares? To whom will these metrics matter? What is being measured and why should that have an impact on the things that really matter to a career in science? Why would a funding agency or a hiring committee accept these metrics as meaningful?

(SNIP)

If you’re hoping to provide a powerful incentive toward participation, you must offer some real world benefit, something meaningful toward career advancement.

And with this, my failure to come up with a good title of this blog post is exposed: it’s not just about peer review. As the title of our working paper already suggests: it’s also about scholarly communication. Who cares? Scholars who want to read scrutinized research literature might care. Authors who want to see their papers scrutinized might care. People who care about Open Access might care. Scholars who want to peer review properly might care. Scholars who peer review properly and want to be rewarded with higher odds of having their own works noticed, read, reviewed and cited might care. Scholars who care about a more efficient allocation of peer reviewers and their peer reviews might care. You can argue against the validity of these “incentives”, but you can’t just disregard them completely without considering them and telling people “there’s nothing for them to gain”. I find that to be a very incomplete approach of evaluating proposals.

Look, there are plenty of legitimate concerns with our proposed model. We spent quite a bit of time addressing how those concerns can be tackled. We could use advice on how to improve our proposed solutions or even criticism of why they don’t work. What we don’t need are people completely ignoring our proposed solutions when they review our proposal. It doesn’t help us, and I don’t see how it can help you. And that’s all I have to say for now. Back to working on part 2.

A Proposal To Improve Peer Review: A Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform (part 1)

Whoa, has it really been a year since my last update? Geez!

“Slacker! Where have you been!?”

I guess I’ve just been distracted. I have, however, not exactly been slacking off…much. As evidence of that I’m presenting our (me and my co-author) working paper that anyone can freely download over at SSRN. (Not giving up on my nick here though)

The title of our working paper is:

Towards Scholarly Communication 2.0: Peer-to-Peer Review & Ranking in Open Access Preprint Repositories.

“Wait, what? If that’s the title of your working paper, then why didn’t you name your blog post like that?”

This blog title is shorter, more befitting of a blog post and essentially conveys the same message: “Peer-to-Peer Review (& Ranking) + Open Access Preprint Repositories” equals our “Unified Peer-to-Peer Review Platform”. And now I’m going to summarize our working paper in such a way that it’ll fit nicely in a couple of blog posts. This way people who don’t feel like reading through 25 pages (right now) can still get the gist of the proposed model. I can’t guarantee that you won’t miss important details, though. In fact, I’m fairly certain you’re going to miss out on good stuff. Let’s start with…

The abstract: